in

my Life

in

my LifePsychologists sometimes define motivation as

persistence at an activity in the face of punishment. By this standard,

my entry into the world of basketball would have to be described as

highly motivated.

During my first two years at college I lived at home, which meant a two-year layoff from basketball. The only ball I played was when my band practiced at my house and we took a break to play "Soul Basketball." Soul Basketball meant playing with heart and style and not worrying about sucking because it was so dark outside that one couldn't easily tell how badly anyone played.

Want to hear about a really stupid self-inflicted injury? Some time during high school I was at the Bellefonte YMCA, I think with my Boy Scout troop. After whatever we were there for, we started a pickup basketball game in our street clothes. I tried playing in my stocking feet, but decided to opt for more traction by taking off my socks. After playing like this for a short time on the cement floor, I developed blisters all over the bottom of both feet.

Another memorable injury was at the YMCA in DuBois when I cut into the middle, took a pass up high, and got a defender's elbow on my brow ridge. Blood all over the place and a few stitches. Finally, only recently, in an informal 3-on-3 game at Rec Hall, a second after I passed off the ball, the guy defending me ran up a made a roundhouse swipe toward me, hitting my pinky finger square on. The pop, the pain, and the funny angle of my finger let me know immediately that I had a dislocation. But far worse hurts than physical injuries have plagued my life in basketball.

Aesthetics. One is the aesthetic of an arcing ball hitting nothing but net, making the characteristic zippppp sound. I find this particularly beautiful when I am shooting the ball, but it is almost as thrilling when someone else hits a perfect shot—even someone on the other team. I also delight in the perfectly placed pass and in the kind of perfect timing that leads to a steal or blocked shot.

Trickery. The second is the delight of tricking your opponent into thinking you are going to do one thing when you are actually going to do something else. This is most beautiful when the deception involves one or more teammates, because the possibilities, complexities, and uncertainties increase. I would much rather pass off on an unsuspecting defense to a teammate for an uncontested lay-up than score myself with a strong, athletic move. On an individual basis, I can't often fake a shot or drive and then lose my opponent by accelerating in an unexpected direction. But when I do, it's such a shock to the other team that they start thinking twice about how to guard me. More often, my deceptions involve moving without the ball until I am obscenely open to take an open shot. I'm forever changing my speed and direction of movement and consequently have earned a reputation for being dangerously sneaky. I love that. I also try to be sneaky on defense by getting the man I'm guarding to think I'm unaware of what he is doing and then cutting into the passing lane to steal the ball. In addition, I try to remain as aware as possible (without making it obvious that I'm aware of anything) of what everyone on my side of the court is doing in order to pick off passes intended for opponents guarded by my teammates.

My strategy for fooling my opponents is to alternate playing predictably and unpredictably. When attempting to play unpredictably I sometimes even try not to know myself what I am going to do. This does backfire sometimes. If I don't know what I'm doing, my teammates don't know either. My occasional unconventional play annoys people who like to play by the book and fosters the perception that I don't know what I am doing. But that's nothing new. The difference now is that when I look inept it is (usually) an intentional ruse.

Physicality. This may sound odd, but the third thing I love about basketball is the somewhat painful physical contact. I love setting a pick on an opponent who weighs about 100 pounds more than I do and have him crash into me. Even though this collision often flattens me to the extent that I can't roll off of him, I find great satisfaction in knowing I have taken him physically out of the play. I also love to box out larger opponents to enable us to get a rebound. At my size (5'8½", 165-170 lbs.), I don't often have a physical advantage over my opponent, but when I do, I will muscle right past or shoot right over the top of him.

Roy Baumeister, a social psychologist at Case Western Reserve University, has an interesting theory of masochism that may apply to this aspect of basketball for me. Roy says that what masochists enjoy about pain is a heightened sense of awareness of aliveness in the present moment. (We're talking about small amounts of pain here, not injury-producing pain.) Dead people don't feel pain, so when you hurt you know you are alive. Or, as Lao Tsu said in chapter 13 of the Tao Teh Ching, "Misfortune comes from having a body. Without a body, how could there be misfortune?" Pure physical experience instantly empties the mind of annoying, incessant, internal chatter. Zen teachers stopped idiotic thoughts by cracking students over the head with staves. I stop my own idiotic thoughts by putting a body on someone.

I recall two peak experiences at the DuBois YMCA. One came during the last, meaningless seconds of a league playoff game that we were about to lose. One of the league's better shooters went up for a jumper from about 15 feet out. I leapt as high as I could, feeling for a moment as if I had superhuman strength, and cleanly swatted the ball out of the shooter's hands. The "Oh!" from the crowd was pretty satisfying, too. A second moment was in 1988 after I had returned from a semester of teaching at University Park, where I had played pickup games in Rec Hall. I had learned a few things and was in better shape after running full-court games at UP. The moment I remember was being challenged by a defender while dribbling at high speed on a breakaway, and executing a perfect cross-over dribble to get past the defender. The taunting response from the players in this case, something like, "oh, where did the professor learn the cross-over dribble?" convinced me that I was done playing there.

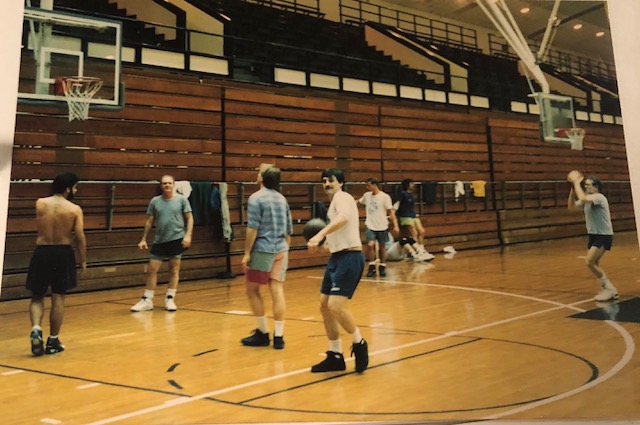

These days are my halcyon, idyllic days of my basketball life. Living in State College since 1992, I've been able to play pickup ball regularly at Rec Hall. The pickup games here are part of a long tradition (30+ years) of friendly play at noon time (actually about 10:45-1:15 on MWF and 11:30-1:00 on TTh). The players range from a few college players through a few guys in their late 60s. An effort is made to create even teams, and with four courts, one can play almost continuously. Best of all, meanness is almost totally absent. This place is heaven.

When I originally wrote this essay (April 27, 1999), I was indeed in the middle of a wonderful phase of my basketball career. Three things were great about this period. First, opportunities for playing basketball were plentiful. In addition to the five games during the week at Rec Hall, I found a game that started at 7:30 A.M. every Sunday at IM building, with enough participants to occupy two or three courts for three hours. Second, nearly all of the players at Rec and IM were great sports who wanted to play fair and have fun. There was very little tension and drama. My only anxiety was getting to these venues early enough to be one of the first ten to insure being in the first game. Finally, my body was in good shape. I was healthy, strong for my size, and almost as fast as I was in my late 20s.

As they say, however, change is inevitable.

Little by little, participation in the games began to decline. By 2010, three or four courts on MWF at Rec Hall had declined to one or two. Lower attendance on Tuesdays and Thursdays meant no more full court, only half court. And by 2014 even half court games became rare. In the wake of the Sandusky scandal, Penn State changed its policies on the use of recreational facilities, allowing access only to holders of a valid PSU ID plus one guest. Although the policy has yet to be strictly enforced, it seems to have had a strong chilling effect on participation from persons without a Penn State ID. It appears that soon access will be made even more difficult with the installation of card-swipe systems. The situation at IM has been particularly dire due to a long-term construction project to expand the facility. There is currently no front entrance, parking has become limited, and there is an electronic lock on the back door that makes entering the building before 8:30 difficult, if not impossible. A number of times we have been unable to get one full court game going on Sunday mornings, and it might die when the construction with new security measures is complete.

Then there's the issue of mid-life aging and health problems. Bouts of diverticulitis in my early 50s kept me off the courts for weeks. In 2009, severe plantar fasciitis prevented me from playing for a month or so. But the worst problems showed up in 2010. First, one day in March I experienced sharp pain in my lower back when getting out of the car to play some half-court. I tried to play anyway—but only for about two minutes. The pain was so excruciating that I could not move at all without a burning fire shooting from my back down my right leg. I was diagnosed with two herniated discs and spinal stenosis and was in pain 24 hours a day for months and months. Physical therapy had absolutely no effect on my condition. Eventually my insurance allowed epidural injections, and after two such injections I was miraculously better and able to play once again. Until, that is, I had a collision at IM that sent me airborne and I landed squarely on both knees, and later twisted my right knee awkwardly on a play, experiencing a sharp pain. I thought I had just sprained ligaments, but my knee did not improve after many weeks and I began to develop swelling from fluid build-up around my knee. I visited an orthopedic surgeon who told me I had severe arthritis and virtually no cartilage left in my knee joints. Steroid shots eased the pain at first, and eventually I got hyaluronan injections for more cushioning. Ultimately, however, I had to accept that there would always be some pain present and would have to learn to play with the pain.

So, these days, in the twilight of my career, I have had to become more and more philosophical about my participation in basketball. I usually play with a fair amount of reserve to avoid further injury to my body. I do not worry any more about arriving early to insure participation in the first game. I still choose to exert myself 100% now and again, carefully choosing my moments. Mostly, though, I focus on relaxing, enjoying the game, and being grateful for every minute that I can still be on the court.

As I sit here, updating my story to include events in the twilight of my basketball career, I also want to mention an important, singular basketball experience that I had in September of 2013. For nearly 30 years I had been longing to attend a workshop at the Omega Institute called Beyond Basketball. Originally run by Phil Jackson and eventually taken over by one of his assistants, Charley Rosen, this basketball camp was designed to teach the Inner Game of basketball. Or so I thought. As often happens in life, things are not always as you expect them to be. Based on articles I read about the workshop, upwards of 30-50 people participated, and registration often closed within days after opening. The workshop was conducted at a gym off-campus, so I pictured dozens of players boarding a bus for the site. I expected drills to be interspersed with lectures and meditations on the mental and spiritual aspects of the game.

As it turned out, there were eight participants. Charley asked if one of us could volunteer to drive half the participants to the gym (he drove the other half in his car). The work was almost entirely drills, with little explicit coaching about the mental aspects of the game. After the day-long workout, I thought we would be going over what happened that day. Instead, the evening discussion session consisted almost entirely of stories and gossip about professional basketball players and typical guy-talk debates about who were the best players and teams in the NBA. In another unexpected moment, I discovered that Charley's passion for basketball was equalled by his passion for literature; we surprised each other by reciting in unison the first 15 lines or so of the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales ("Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote, The droghte of Marche hath perced to the roote . . . "). (I had to memorize these lines for my 10th grade English class and I never forgot them.)

Although the camp turned out to be different from what I expected, I was not disappointed. By this point in my life, I had fully embraced the idea that expectations are premeditated resentments. Even though the experience was different from what I had imagined, I thoroughly enjoyed the workshop and wrote about it in detail elsewhere. Today, in the twilight of my basketball career, I continue to apply, as best I can, what I know about joy on the court to everyday life. That was the take-home message from Beyond Basketball.

Finally, in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic shut everything down. There was

no basketball anywhere for the longest time. I tried playing at IM

during the spring semester of 2021, but managed to play in a game only

several times. People were just not showing up. Eventually, only Wade

Shumaker and I were there at noon. We shot baskets for awhile, waiting

for the other players that never materialized. In May of 2021 we

managed to get some of us together a few times to play on the outdoor

court at Sunset Park. And then, nothing again. We chatted through our

email list about intentions to return to Rec Hall in the fall if the

building would reopen to us. Not enough people expressed an interest in

playing at IM, so the reopening of Rec Hall was our only chance. But

Campus Recreation was silent on that possibility until finally an

administrator responded to an email I sent in August 2022. That

conversation is below.

Finally, in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic shut everything down. There was

no basketball anywhere for the longest time. I tried playing at IM

during the spring semester of 2021, but managed to play in a game only

several times. People were just not showing up. Eventually, only Wade

Shumaker and I were there at noon. We shot baskets for awhile, waiting

for the other players that never materialized. In May of 2021 we

managed to get some of us together a few times to play on the outdoor

court at Sunset Park. And then, nothing again. We chatted through our

email list about intentions to return to Rec Hall in the fall if the

building would reopen to us. Not enough people expressed an interest in

playing at IM, so the reopening of Rec Hall was our only chance. But

Campus Recreation was silent on that possibility until finally an

administrator responded to an email I sent in August 2022. That

conversation is below.| Subject: | Rec Hall South Gym availability in the fall |

|---|---|

| Date: | Thu, 21 Jul 2022 08:45:37 -0400 |

| From: | John A. Johnson <j5j@psu.edu> |

| To: | campusrec@psu.edu |

--

John A. Johnson

Professor Emeritus of Psychology

Penn State University

https://www.personal.psu.edu/~j5j/

| Subject: | Campus Recreation Membership - IM Building |

|---|---|

| Date: | Wed, 10 Aug 2022 15:43:08 -0400 |

| From: | Buonanno, Linda M <lmb449@psu.edu> |

| To: | Johnson, John Anthony <j5j@psu.edu> |